Vitiligo incidence and prevalence

Around 100 million people around the world are affected by vitiligo with

a prevalence of around 0.4–1.6%.2–5

Non-segmental vitiligo accounts for 84–95% of vitiligo cases.6

Vitiligo is often misdiagnosed or under-reported, leading to an underestimated prevalence.5,7 According to a global survey, almost half of patients with vitiligo were previously misdiagnosed.*7

Vitiligo global demographics

Vitiligo affects men and women equally, although prevalence is slightly higher in females. Most patients will experience the onset of vitiligo by the age of 30 and around 70% of diagnosed patients will have facial involvement.4,5,8–11

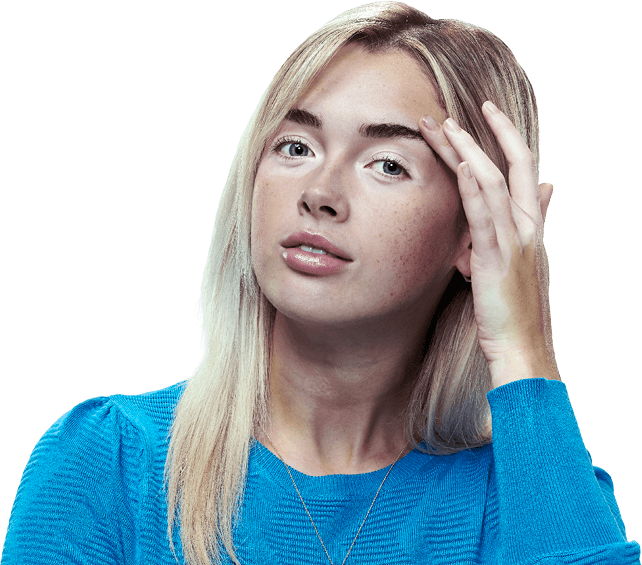

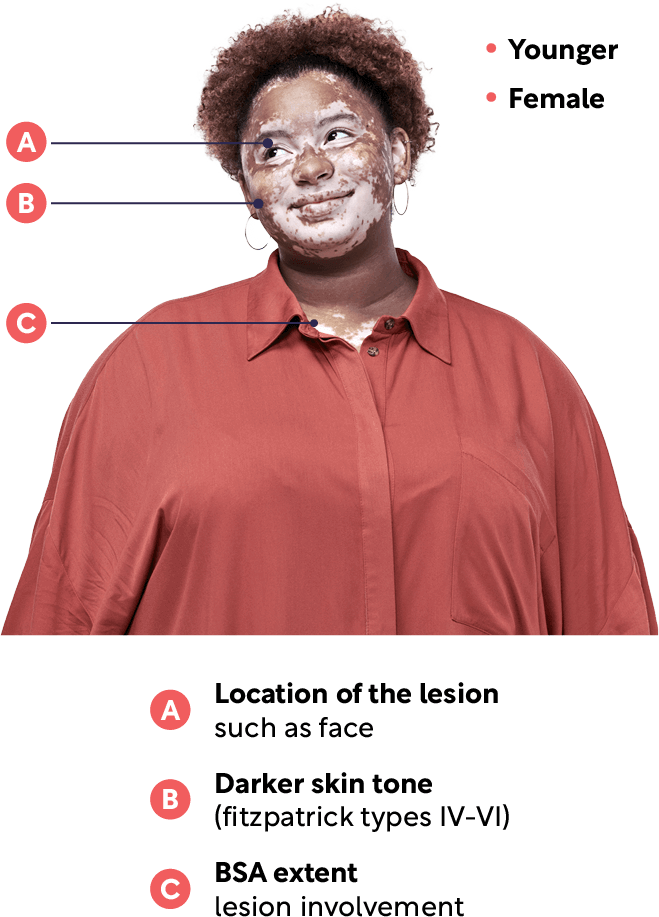

Psychosocial impact may be more likely in certain patients12

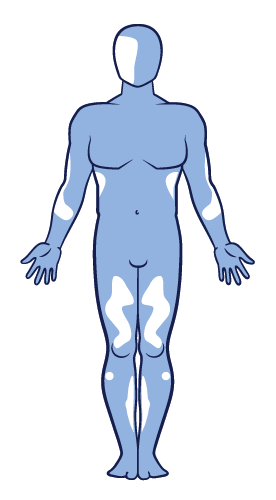

The most commonly affected body areas for patients diagnosed with vitiligo include the face, hands, wrists, feet and ankles.5,8

A global survey also looked at vitiligo prevalence according to skin types, using the Fitzpatrick Skin Grading Scale. Phototype III was the most common, followed by phototype IV, II and V. There were fewer participants with phototype I.5

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune skin disease13

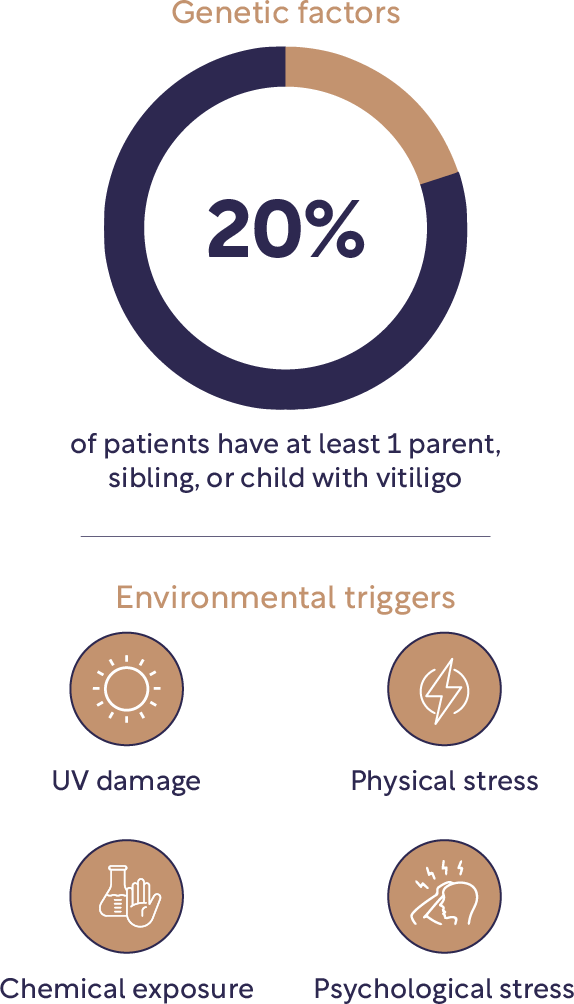

It is believed that the progressive destruction of melanocytes that results in vitiligo is caused by a dynamic interplay between several factors, including environmental triggers, a dysregulated immune system and genetic susceptibility.2,22,23

Genetic predisposition for vitiligo may be triggered by environmental factors2,13,24,25

Environmental triggers

Vitiligo is a complex condition that can appear without apparent triggers. However, depigmentation can also occur after an injury to the skin, emotional or physical stress, severe sunburn or sun damage, or exposure to some chemicals. These events can stimulate oxidative stress in pigment cells and initiate an innate immune response.26

Genetic susceptibility

Genetic factors are known to play a key role in the development of non-segmental vitiligo and studies have discovered nearly 50 genetic loci that contribute to vitiligo risk, including those located on chromosomes 4q13-q21, 1p31, 7q22, 8p12 and 17p13.13,22 Genetic mutations cause melanocyte susceptibility to oxidative stress and around 20% of patients with vitiligo have at least one parent or child with vitiligo.13

The genes associated with an increased susceptibility to non-segmental vitiligo are also linked to other autoimmune diseases.13

Dysregulated immune system

The destruction of melanocytes in non-segmental vitiligo is complex and multifactorial with immune dysregulation and inflammation playing a key role.13,27

Research indicates that autoantibodies might develop due to a genetic predisposition to immune dysregulation and dysfunction of T regulatory cells. This dysregulation leads to the T cell-mediated autoimmune destruction of melanocytes.13,27

Vitiligo and melanocytes

Melanocytes can be found in the basal layer of the epidermis and produce melanin, as well as having a role within the immune system. Generally, melanocyte numbers remain consistent (around 5–10% of the cells in the basal layer), however destruction of melanocytes leads to skin depigmentation and vitiligo.22

The JAK-STAT signalling pathway drives non-segmental vitiligo initiation, progression and persistence. During the initiation of vitiligo, melanocyte stress is triggered and an innate immune response is activated. This leads to melanocyte-specific CD8 + T cell stimulation, the release of IFN-y and the initiation of IFN-y JAK1/2 STAT1-CXCL9/10 driven inflammation, which causes the progressive loss of melanocytes.2,23,28–33

Disease persistence and continued melanocyte loss is maintained by memory T cells that require IL-15 mediated by JAK 1/3.2,28–30,34–38

Vitiligo is associated with various autoimmune comorbidities39–41

Autoimmune conditions associated with vitiligo39–41

Non-segmental vitiligo is associated with various other autoimmune conditions with some of the most common conditions being alopecia areata, affecting around 0.5–12.5% of people with non-segmental vitiligo, hypothyroidism, which affects around 10.6% of people, and psoriasis, which affects around 7.6% of people with non-segmental vitiligo.39,42–44

Other conditions include multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, pernicious anaemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, lymphoma, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, seronegative arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.39,42–44

Vitiligo classification: non-segmental, segmental and mixed-type vitiligo

There are several different types of vitiligo with different classifications and nomenclature.¶

Non-segmental vitiligo

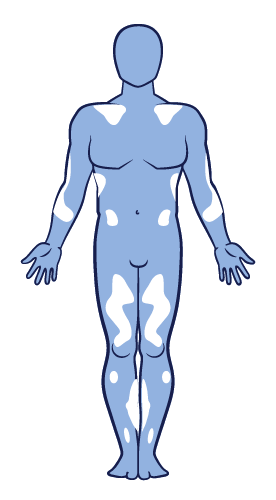

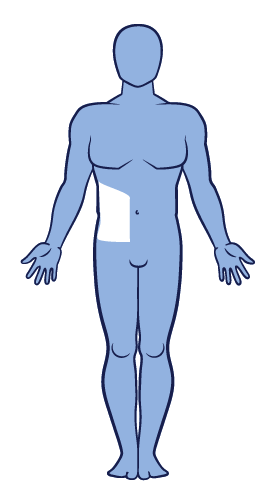

Non-segmental vitiligo is an autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks functional melanocytes. It is the most common type of vitiligo and presents with lesions involving both sides of the body in a symmetrical distribution. This results in depigmentation of the skin, typically presenting with non-scaly, chalky-white macules. 13,27,45–47

Non-segmental vitiligo is characterised by slow progression and an unpredictable course. ‘Vitiligo’ is often used as an umbrella term for all forms of non-segmental vitiligo, but not segmental vitiligo. 6,13,45

Other terms for non-segmental vitiligo

Non-segmental vitiligo is also sometimes called generalised vitiligo, bilateral vitiligo and vitiligo vulgaris. Non-segmental vitiligo can include acrofacial vitiligo, which affects the lips, face plus hands and feet; focal vitiligo, which affects only a small area of the body; or universal vitiligo, where most of the body loses pigmentation.45

Segmental vitiligo**

Segmental vitiligo is related to somatic mosaicism and is not believed to have an immune aetiology.13 It is usually unilateral with earlier onset and it progresses rapidly before stabilising. It is generally less progressive than non-segmental vitiligo. Segmental vitiligo is distinguished from other types of vitiligo because it has distinct underlying pathogenetic mechanisms and shows poor response to conventional treatments.6,13,45

Mixed-type vitiligo**

Mixed-type vitiligo presents with segmental lesions, followed by bilateral lesions and it is usually more refractory to treatment than the non-segmental form.6,13,45

**Opzelura® is indicated for the treatment of non-segmental vitiligo with facial involvement in adults and adolescents from 12 years of age1

Leucoderma and vitiligo

Additional nomenclatures of vitiligo include leucoderma (sometimes spelled leukoderma). Leucoderma is a loss of skin pigmentation and vitiligo is a specific type of leucoderma but the terms are often used interchangeably.48

Additionally, leucoderma punctata is a term used to describe a type of vitiligo characterised by small depigmented spots.13 The umbrella term of leucoderma is also sometimes used to describe a specific form of chemical leucoderma, where hypopigmentation is caused by repeated exposure to chemicals rather than an autoimmune condition.49

The unmet need for vitiligo repigmentation therapies

Until the approval of Opzelura®, there were no licensed treatments for non-segmental vitiligo in the UK and the British Association of Dermatologists Guidelines 2022 recommended a combination of topical therapies with phototherapies for disease management.50

Management options for vitiligo include corticosteroid cream (topical corticosteroid [TCS]), topical calcineurin inhibitor (TCI), narrow-band (NB)-UVB plus TCS and TCI, immunosuppressants with TCS, excimer laser and TCI for localised vitiligo, surgery for stable segmental or non-segmental vitiligo on hands and feet and depigmentation for extensive vitiligo.50

While used in some EU countries, psoralen cream and UVA (PUVA) for vitiligo, is not included in current UK guidelines.50

Limitations of vitiligo management options include low quality repigmentation, depigmentation relapse, uneven responses to different body regions, low adherence and limited tolerability.

- Low quality repigmentation: Medical monotherapy or combination therapy reduced the likelihood of cosmetically acceptable repigmentation vs monophototherapy51–54

- Depigmentation relapse: Monotherapy and combination therapies were associated with stable repigmentation over a period of 3–6 months with relapse rates of up to 67%55–58

- Uneven responses to different body regions: Regardless of treatment regimen, acral lesions showed low repigmentation response vs face and neck59–61

- Low adherence: Around 70% of patients with vitiligo showed low adherence to medication due to lack of efficacy, long treatment duration, dosing frequency, financial burden and patient dissatisfaction62–64

- Limited tolerability: Steroids are not recommended long-term due to weight gain, and TCIs are associated with local reactions, including burning sensation, pruritus and erythema.50,66 Laser therapies and NB-UVB can cause burning sensations, pruritus, erythema and treatment site pain67,68

Currently there are no biologics approved as a treatment for vitiligo.

Opzelura®, which contains ruxolitinib, is the first and only approved therapy for non-segmental vitiligo repigmentation – meeting the unmet need for a treatment for non-segmental vitiligo patients that helps with repigmentation.1,50,69

Opzelura® and repigmentation

Opzelura®, a JAK 1/2 inhibitor, has been found to inhibit depigmentation and induce repigmentation.1,28,70 Results in clinical trials found that after 52 weeks, 52.6% of patients achieved a 75% improvement in facial repigmentation and 53.2% of patients achieved >50% improvement in overall body repigmentation.71

Opzelura® has been well tolerated, with no serious adverse events reported.71 Find out more about the repigmentation efficacy of Opzelura® for your patients with non-segmental vitiligo.

Opzelura® is contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding.1

*From a global online survey on the burden of vitiligo from the perspective of patients with vitiligo (n=3,541) and the HCPs who treat patients with vitiligo (n=1,203).

†Meta-analysis of five case control studies of patients with vitiligo and depression (N=461).

‡Study of 1,123 patients with vitiligo from 21 hospitals and clinics in Korea to determine the effect of vitiligo on QoL using Skindex-29.

§Survey of 80 patients with vitiligo attending a private skin clinic in Tehran, Iran, using the Illness Perception Questionnaire.

¶Opzelura® is only indicated for the treatment of non-segmental vitiligo with facial involvement in adults and adolescents from 12 years of age.

††Patient quotes are fictional.

Abbreviations

BSA, body surface area; CD8+, cluster of differentiation 8 positive; CXCL9/10, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9/10; IFN-ɣ, interferon-gamma; IL-15, interleukin-15; JAK-STAT, Janus kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription; NB-UVB, narrowband ultraviolet B; PUVA, psoralen ultraviolet A; QoL, quality of life; TCI, topical calcineurin inhibitor; TCS, topical corticosteroid.

References

- Opzelura® (ruxolitinib cream) Summary of Product Characteristics. Incyte Biosciences UK Ltd.

- Bergqvist C, et al. J Dermatol. 2021;48:252–270.

- VR Foundation. About Vitiligo. Available at: https://vrfoundation.org/about_vitiligo (Accessed December 2024).

- Krüger C, et al. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1206–1212.

- Bibeau K, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:1831–1844.

- Picardo M, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15011.

- Bibeau K, et al. Presented at: Maui Derm for Dermatologists, 24 January 2022, Maui, HI.

- Talsania N, et al. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:736–739.

- Gandhi K, et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:43–50.

- Patel R, et al. Dermatology. 2023;239:227–234.

- Ezzedine K, et al. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:134–139.

- Ezzedine K, et al. Am J Clin Derm. 2021;22:757–774.

- Bergqvist C, et al. Dermatology. 2020;236:571–592.

- Patel KR, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:191–197.

- Wang G, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1343–1351.

- Bae JM, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:238–244.

- Firooz A, et al. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:811–814.

- Elbuluk N, et al. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:117–128.

- Ezzedine K, et al. Presented at: European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 29–31 October 2020, virtual.

- Silverberg JI, et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:159–164.

- Dauendorffer JN, et al. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2022;149:92–98.

- Said‑Fernandez SL, et al. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(4):312.

- Rashighi M, et al. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257–265.

- Boniface K, et al. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):52–67.

- Silverberg JI, et al. Cutis. 2015;95(5):255–262.

- Faraj S, et al. Clin Exp Immunol. 2022;207(1):27–43.

- Spritz RA, et al. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:245–255.

- Strassner JP, et al. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;43:81–88.

- Richmond JM, et al. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:676–682.

- Frisoli ML, et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020;38:621–648.

- Howell MD, et al. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2342.

- Rosmarin D, et al. Lancet. 2020;396:110–120.

- Martins C, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142:1194–1205.

- Chen X, et al. Free Radical Biology Med. 2019;139:80–91.

- Richmond JM, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10(450):eaam7710.

- Atwa MA, et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:2640–2644.

- Nolz JC, et al. Mol Immunol. 2020;117:180–188.

- Riding RL, et al. J Immunol. 2019;203:11–19.

- Hadi A, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:628–633.

- Gill L, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(2):295–302.

- Korde S, et al. MVP J Med Sci. 2018;5(2):125–133.

- Sheth VM, et al. Dermatol. 2013;227:311–315.

- Dahir AM, et al. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1157–1164.

- Yuan J, et al. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;9:803.

- Ezzedine K, et al. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:E1–13.

- Rodrigues M, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:17–29.

- Ezzedine K, et al. Lancet. 2015;386:74–84.

- VR Foundation. Which skin conditions can be mistaken for vitiligo? Available at: https://vrfoundation.org/faq_items/which-skin-conditions-can-mimic-vitiligo (Accessed December 2024).

- Ghosh S. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55(3):255–258.

- Eleftheriadou V, et al. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:18–29.

- Parsad D, et al. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:942–945.

- Kwok YKC, et al. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:104–110.

- Yones SS, et al. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:578–584.

- Zhang XY, et al. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2010;26:138–142.

- Boone B, et al. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:55–61.

- Kumaran MS, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:269–273.

- Doghaim NN, et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:142–149.

- El Mofty M, et al. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:406–412.

- Bae JM, et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:666–674.

- Stinco G, et al. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2013;3:95–105.

- Lee JH, et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:929–938.

- Abraham S, Raghavan P. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2015;77:8–13.

- Alsubeeh NA, et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:2029–2038.

- Eicher L, et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:2253–2263.

- Rath N, et al. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:357–360.

- Sisti A, et al. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:187–195.

- Hari Kishan Kumar Y, et al. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:162–166.

- Mohamed HA, et al. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2015;17:216–223.

- Hospital Pharmacy Europe. Ruxolitinib cream gains MHRA approval for non-segmental vitiligo. Available at: https://hospitalpharmacyeurope.com/clinical-zones/dermatology/ruxolitinib-cream-gains-mhra-approval-for-non-segmental-vitiligo/ (Accessed December 2024).

- Birlea SA, et al. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(2):205–218.

- Rosmarin D, et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(16):1445–1455.

UNITED KINGDOM

Adverse events should be reported.

Reporting forms and information can be found at:

www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard or search for MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store.

Adverse events should also be reported to Incyte by calling 00-800-0002-7423.

REPUBLIC OF IRELAND

Adverse events should be reported.

Reporting forms and information can be found at HPRA Pharmacovigilance:

www.hpra.ie. Adverse events should also be reported to Incyte by calling

1800‑456‑748.